When I was in academia, March was the hardest month. Judging from the conversations I have been having with clients recently, that is still true. There is something about the uphill slog to Easter, through the bulk of the Spring teaching, with increasingly stressed dissertation students, committees starting to plan for the next year (and rising anxiety about next year if you are precarious), at the same time as late dawns, early dusks, and wintery weather disrupting commutes. Returning to campus after the Easter break was always a transformation into warm sun and blossom, quiet classes as student attendance tailed off, and anticipating the long summer ahead.

Perhaps because I primarily work with academics, my late Feb – early March this year has been reminiscent of former academic springs (too reminiscent if I am honest). I have found myself rushing. Slipping in my eating habits. Feeling pressured, and resentful about the pressures. Not sleeping enough. I am in the process of take a long hard look at myself and my attitudes toward life (you can read more about this over on Substack…) but in the meantime, I am acknowledged a very real need to get back to basics – to the fundamental principles of self-care and wellness that must underpin our daily living if we want to remain healthy and emotionally whole, even in busy or trying times. So March’s blog is by way of a little reminder, in case you too are finding yourself overwhelmed and under-resourced...

In case you were wondering, I wrote the above in early March. It is now April 21st. So what happened…

Well, life happened.

An unexpected house guest arrived for a month. Suddenly, what had already been a very busy season with multiple workshops and classes was taking place against a backdrop of change in the home – an extra body, less space, more needs and demands, less quiet (a lot less). I work from home, so in reality this meant a dramatic collision of domestic and career responsibilities, quite literally being able to hear my houseguest talking whilst I was on calls with clients or trying to prep material. There was also the strain of a foster cat not settling, and our own cats’ distress at her presence.

Honestly, it has been the toughest month I remember since my husband was in hospital three years ago. In the midst of the stay I decided to get some space for myself and booked into an air bnb on the coast, taking only the dog, walking clothes, my laptop, and some books. I ended up staring at the sea for hours, entranced by the changes I could literally watch from the windows of my holiday let. I felt my mind and soul settle again, was able to connect back in to calm and clarity, could be honest about my emotions and exhaustion without having to keep a smiling face on all the time. It wasn’t enough, but it topped me up for the final eight days of the visit, which are now coming to a close. In a serendipitous coincidence, the foster cat is also leaving us tonight to go to her forever home – upstairs from us with the neighbours (yes, we are those people who force needy cats on cat-free people). So by the time this blog is posted, we will be back to normal – two humans, two cats and a puppy, five little lives, a lot more quiet.

But let’s talk about what happened this month, because being so totally derailed by a house guest may strike you as an extreme reaction. Some readers may be blessed with extrovert natures or family traditions of doing everything together and see a month with the mother-in-law as a normal experience. I am not one of you – I say this sadly, I would love to be the unflappable hostess who is thrilled to be surrounded by people all the time…but then, I wonder why I want to be that person? Because she appears more virtuous, more generous, more worthy of my admiration than someone who is hsp and an introvert and needs quiet and her own space in order to stay sane. We create these hierarchies of character (and mental health, because inevitably someone will start to pathologise at this point), and the cat-lady who would rather be alone with books does not rank as highly on that list as the woman (yes, definitely a woman) who cooks and cleans and chats and ferries people around the country and is always bouncy and still keeps all her hats spinning, unmoved by the extra demands of others.

My trip to the coast was insightful for me because once there I immediately dropped back into healthy habits without having to think about it – I ate well, I slept, I took slow mindful walks with the dog, I wrote, I dozed and watched documentaries, I listened to podcasts in the bath, I called friends, I reflected on my practice. Everything that I know anchors and sustains me was ready at my fingertips the moment I had space to connect to it. So when I frustratedly censure myself for being derailed by the visit, that isn’t actually true – that is my shame talking again, the voice of my inner critic who thinks I should be able to maintain my self-control and perfect practice even when life happens. I was not derailed, not really – work continued to happen at a reasonable standard, I kept learning and growing, kept writing over on Substack, kept walking the dog. But I was thrown off by the presence of someone else in my space with different habits to my own, whose being there made it harder to maintain my everyday patterns of self-care, rooted as they are in a normal that is much much quieter. Of course I struggled to eat a diet that I know works for me when there was an older relative with different expectations in the house. Of course I lost momentum on exercise when I was so exhausted from being responsive to someone else all the time. Of course I struggled emotionally when my normal avenues for rest, like crashing in front of a movie for two hours, couldn’t happen because there was someone else already on the sofa watching their own shows.

Life happens, and it affects us. This is called being human. And I always said Beatha Coaching was about the reality of being human – the simple vulnerabilities and ups and downs of life and how we respond.

Let’s divert for a moment to the science of the thing, since I know that is what you are really here for. When we experience stress, danger, or trauma, our brains are predictable. They draw on ancient systems for response as well as our own unique store of memories and knowledge.

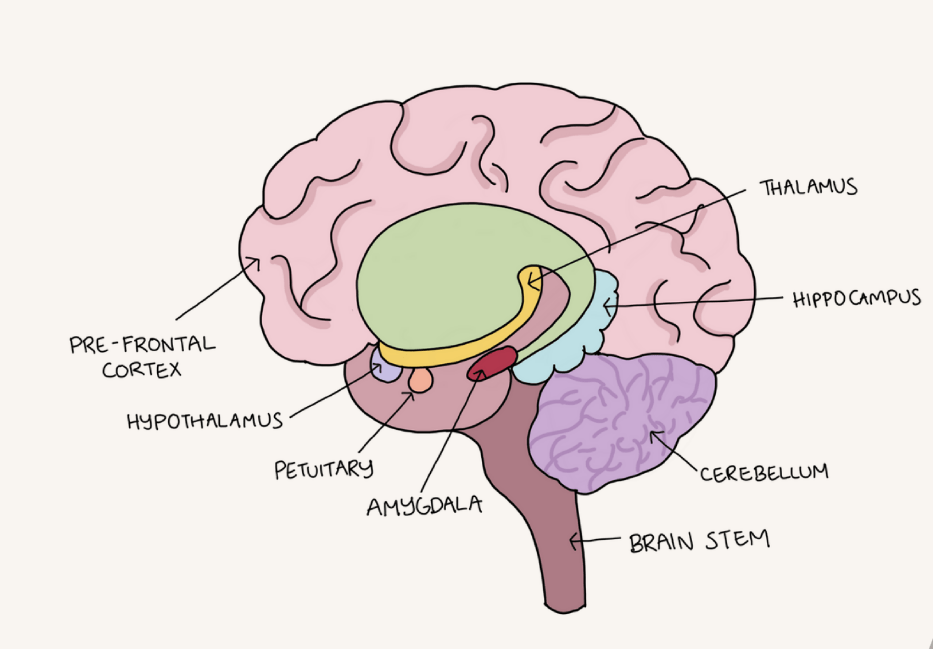

First comes the fast track. As the thalamus receives information from our senses, it is in constant conversation with the amygdala. The amygdala is like our brain’s early warning system – it reacts quickly and efficiently to any risk of danger. If the amygdala detects a threat, it immediately sends a signal down our brain stem to the adrenals, located just above the kidneys, telling them to release stress hormones and get the body activated. That’s the jolt of nervous energy you feel when you think you have lost the car key, or you smell the perfume your old bully wore, or you hear a relative talking loudly outside your office door when you are on a coaching call (for example…).

A moment after the fast track is complete, so once you are already activated, the amygdala sends a signal the other direction, up to the pre-frontal cortex, to check in about the threat. This is because the amygdala doesn’t have access to all the information the PFC does. The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus where memory is processed, primarily uses fear-based memories for risk assessment – in other words, it’s entire job is to look for and protect us from danger. But the PFC can access a lot more sophisticated information to work out whether we need to be in an alert mode or not. If the PFC decides we can come out of our stress response, it releases GABA, which tells the amygdala to go offline. However, if our analysis is that yes, actually, this is a stressful or dangerous situation, the signal goes back down to the amygdala to keep the reaction going. This signal results in the release of cortisol, which maintains activation. (If you experience anxiety, you will recognise the jittery, activated feeling of being always ‘switched on’ and how quickly it can escalate toward panic).

And this is where things get really interesting, because the information the PFC uses to assess a threat is highly biased toward our past experiences and core limiting beliefs. I know it would be lovely if our front brains were purely rational, the vulcan to our limbic brain’s human, but they can only work with the information we have received and stored in the past. That means that if what we are going through is triggering old memories of being scared, overwhelmed, lonely, or upset, then our PFC will recognise the situation as something we need to stay alert for. What’s more, it will also access the same neural pathways we have used in the past to survive. So if, say, you were a highly sensitive child who found noise overwhelming, and you managed that threat by being alone as much as possible, your instinctive reaction to noise will be to retreat. Similarly, if you have experienced painful rejection when you didn’t fit in with others’ needs, you may feel strongly driven to appease those around you, and not trust reassurance that you are loved as you are.

You might have already picked up on a few things about my reaction that give you some cues as to why I was overwhelmed this month – firstly, I respond particularly strongly to sound and smell, and there was a lot more sound fairly constantly surrounding me, as well as several foreign smells that I am not used to in my home. Combined with this, my home is also my work place, so I was being affected in every aspect of my day. In addition, I had limited access to my safe places and safe practices for the month – as an introvert I recover through time alone, and could only obtain that by leaving the house for a dog walk or by hiding in my office. The latter triggered memories of my teenage years for me and a sense of being pushed out or excluded from parts of my own home. We have already addressed some of my core limiting beliefs about myself as an introvert, and the fact that I can easily experience shame when I am ‘not coping’. All of these combined to mean that my threat system was pretty constantly aroused. It wasn’t a serious situation in the grand scheme of things, but it was an assault on my nervous system without access to all the usual ways that I regulate.

When our brain puts us into alert, and we have a reduced capacity for regulation, we are living in a narrower window of tolerance. If you think of the window as the space between a context that feels intolerable and our healthy coping tools, when external stressors increase and access to regulation decreases we move more quickly outside our window and into a stress response. The window is also affected by the duration of the experience – the longer it goes on, the narrower the window (this is simple biology, adrenaline and cortisol are draining because they keep us out of rest and digest where recovery takes place, so over the long-term stress literally affects our physical body and ability to regulate). You can notice the signs of a window narrowing in exhaustion, lowered appetite, lowered mood, quick escalation of irritation, anger, or tears, lowered immune response, loss of joy in activities we normally love. If you think this sounds suspiciously like burnout – bingo! That is exactly what burnout is, and what causes it.

Let’s start to put all this together:

- Life happens, and we don’t always (usually) have the control we would wish. You are not immune from being affected by the actions and needs of others, or the context you are living and working through.

- The brain responds predictably to stressors through the fast track and slow track. Because of the fast track you will already be activated when the PFC gets involved and starts checking if the threat is real.

- The brain uses past information and coping strategies to manage stress, these may or may not be relevant or helpful, but it can only use what it knows.

- Your past experiences and limiting core beliefs will shape what you feel able to cope with in the day to day.

- When stress increases it can be managed (to some extent) by accessing additional resources that you know work for your nervous system to bring you back into rest and digest. If your access to those resources is limited or reduced you will have a narrowed window of tolerance, and will be able to cope with even less whilst staying regulated.

- A narrowed window of tolerance over a longer period of time means more time in activation which means more pressure on your systems and a shift toward burnout.

Conclusion: you are human, and shit happens.

As I write this, my house guest has left, the foster cat is safely settled in her forever home, I am back on my (decrepit, soon to be replaced, hurrah) sofa to write this, and the house is (reasonably) quiet. But I just had to cancel a yoga class with 30 minutes notice because I sat down and couldn’t stand up again. I walked out of the kitchen leaving the back door wide open, and we have house cats who can’t go outside. I shouted at the puppy for whining at me when I was trying to write. I want to eat nothing. I want to watch nothing. I only want to sleep. I hate myself quite a bit.

Because you don’t just feel better when the stressors dissipate. You then have to do the repair work, the coming back to yourself, your practices, your healing – and accept that you now need to rebalance by spending more time on them to make up for the deficit you have spent during the endurance. Especially if you are someone who ‘copes’, this is going to take just as much effort as getting through the challenges. And it can also feel less legitimate – the crisis is over, so now it’s back to life as normal. But actually, during the stressful periods, your coping techniques will be just that, for coping. They don’t do enough to repair the damage, they only keep you going and reasonably healthy. So now you need to invest more time in all the things that make a difference – healthy meals, sleep, daylight, play and recreation, social connection, joy. You know you are recovering when you can feel pleasure in the little things again, feel more energised and stronger in your body, have a healthy appetite, and can fall and stay asleep easily.

I hope this blog post has given you just a little more information about how your brain actually responds to the world, and that that information in turn helps you to feel more equipped and more compassionate with yourself when life gets in the way. Please leave a comment and let me know how you are doing, and what else I can write about to support you.

Leave a comment