We all know it, we’ve all felt it. Academics talk flippantly of imposter syndrome, and it seems to be a generally accepted aspect of working in the sector. This phenomenon is also true of the cultural and creative sectors, with whom academics have more in common than they might generally accept. Any time we put ourselves into our work and present it to others for assessment we are likely to feel the risk of rejection. Understanding imposter syndrome and how to respond to it is therefore a vital skill for any academic, and yet we rarely talk about what imposter syndrome really is and how it shows up in our body and brains.

Image © Rebekah Ballagh Journey to Wellness

What is imposter Syndrome?

Imposter syndrome is a belief that we are not enough/good enough/performing well enough, regardless of evidence. It is a felt sense of inadequacy, that is held in the body in a highly activated nervous system, and in critical thoughts.

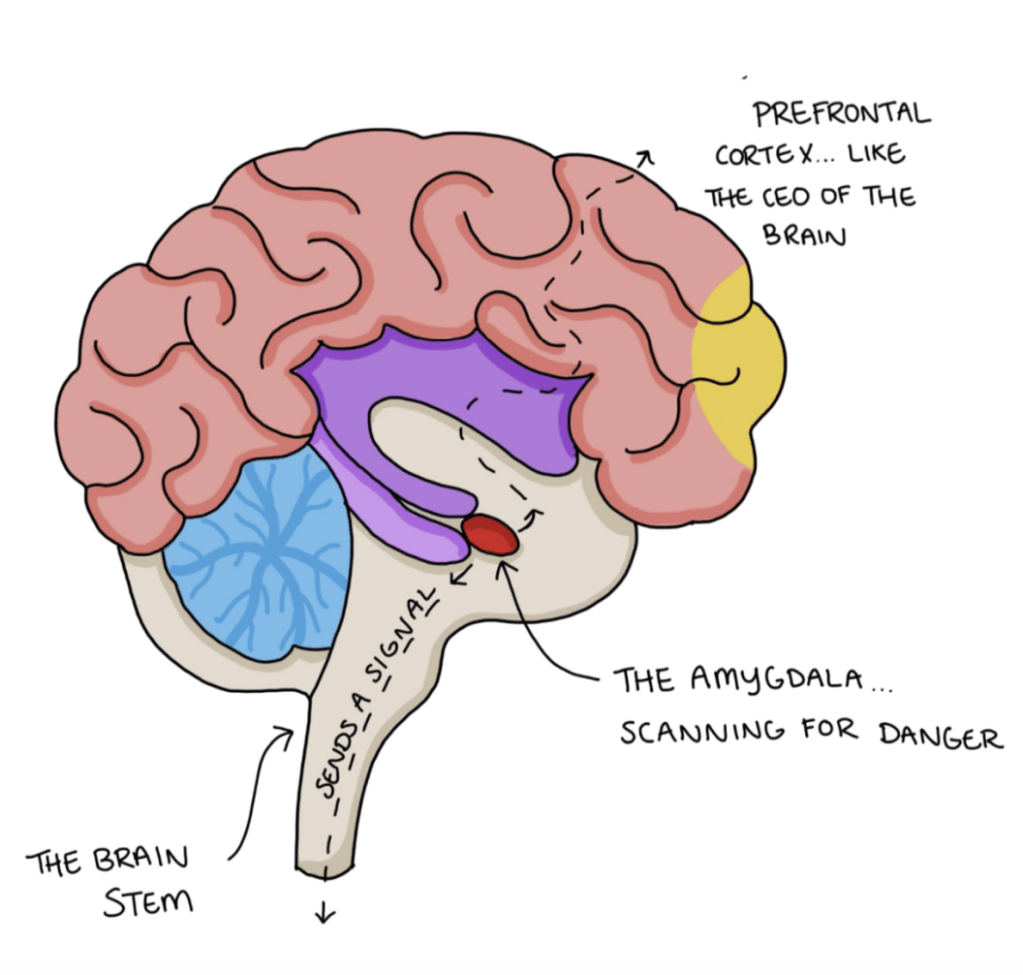

Imposter syndrome derives from our brain’s attention to cues of safety, in particular social safety, and as such emerges from a completely normal and healthy part of our psychology. As infants we initially develop our basic survival skills, coordinated through the brain stem, such as breathing and other regulatory responses; we then develop our limbic system, located just above the brain stem in areas such as the amygdala and hippocampus. The limbic system is responsible for developing social responses, and for identifying good and bad. When a baby begins to focus on human features, and to respond to facial expressions and tones of voice, their limbic system is developing. Finally the brain develops the language centres and prefrontal cortex (PFC) where evaluative thought, self-control, empathy, and complex reasoning reside, and these structures continue to develop until around the age of 21 in females and 24 in males. Working together in integration, these three systems enable us to identify if we are safe, if we are in positive social situations, and whether we can learn, problem solve, and empathise. When we are in integration, we will feel calm and connected to our environment, be able to rationally respond to challenges, and be attuned to the individuals around us.

But what happens if we sense that we are not safe? In situations of extreme danger, such as a car hurtling toward us, our nervous system will snap into action and activate the fight/flight response to enable us to get out of the way. In this scenario, we drop instantaneously out of integration and into our limbic system (identifying danger) and brain stem (activating our adrenals and muscles to push us out of the way). Our PFC is offline until the danger is past – we don’t want to hesitate to problem solve and find ourselves mown down whilst we wait to respond. If our limbic system senses that we are not socially safe, a very similar if more muted response occurs. As infants we learn that the attunement of our caregivers to our needs, and our attunement to their moods, ensures alleviation of our distress if, for example, we are hungry, cold, or scared. Our limbic system learns and internalises these experiences in the hippocampus, taking particular note of times when our needs were not met. These fear based memories are encoded into the amygdala which pulls on them in order to identify danger. As we grow, our limbic system programmes future responses to indicators of rejection, identifying them as a threat to our safety. If we are bullied at school, for example, the denial of attunement from our peers, and the unpleasant experience of exclusion and rejection, results in similar fear reactions to a physical danger. We likely drop out of full integration, with symptoms of activation such as a pounding heart, feeling sick, surging emotions, perhaps an impulse to fight back or to run, or we may feel so overwhelmed that we freeze and go numb. Over time we may also learn to adapt our self-presentation in such a way that we are accepted in the group, to ensure our safety.

As adults, our prefrontal cortex is fully developed and we are better able to regulate our emotions and rationally evaluate indicators in our social environment before reacting. However, the basic functioning of our brain remains the same. And as adults, we are arguably in more complex social situations than we were as children, with more triggers and conflicting sources of information to contextualise and evaluate. Our cues of social safety as adults will come from a range of sources: our family of origin, our class and community background, our education, our status in the society within which we live, the norms of our local neighbourhood and region and nation, and systemic markers of privilege and disadvantage . Workplaces also have unique and contextualised cultures that communicate codes of inclusion and belonging, and these are usually directly tied to real risks such as losing employment. It is therefore more likely that we will experience anxiety at signs of rejection and find ourselves dropping out of integration if our workplace appears to be hostile or challenging.

The felt sense of inadequacy that many academics experience therefore derives from our limbic system’s assessment that we might not be entirely safe in this environment. Thinking about how the (UK) HE sector generates and communicates security, academics are continually under pressure to produce evidence of their value in a system that is marked by inequality and precarity. Systemic issues such as racism, sexism, and ableism (which I have written about in more detail here); scarcity culture and high levels of competition for every post; a legitimised practice of criticism and public shaming accompanied by unacknowledged privilege; continual assessment through REF and TEF, as well as job and promotion panels, grant applications, and gatekeeping of journals; and an unhelpful discourse, at least in the arts and humanities, that ‘failure to thrive’ in academia is tantamount to a future of unemployment. All of these normalised and systemised patterns provide constant cues for our limbic system that we are not socially safe in the academy, and that there are very real risks to being rejected by our peers.

Imposter syndrome in practice

So far I have concentrated on the neurobiology of rejection awareness and sensitivity. These reactions become imposter syndrome once we start to internalise our experiences of precarity and risk, and to look for ways to protect ourselves. The key here is that rather than looking outward at the contextual factors shaping the environment, when we struggle with imposter syndrome we look inwards – our responses to rejection are to feel shame, and to form a tacit agreement with the critical voices (and unequal standards). In effect, we personalise a wide range of factors that may or may not be within our control, making ourselves responsible for minimising the risks to our safety.

Consider the following, probably familiar, scenario. You write a draft article and are excited by the research and the ideas you have developed. The process is stimulating, and you enjoy a few months of research and deep work. You have a journal in mind, but before submitting you decide to get some feedback from a few peers. You send it to range of colleagues and friends you think might be interested. The feedback comes back, and it is a mixed bag. One reader loves it and thinks it is ready to go; one is slightly critical of your framing but thinks it’s an easy solve; one reader, who has more academic clout that the others because they have a strong record of funding, sees many issues with the piece, offers an extensive reading list, and is clearly confused that you think the article is ready to submit.

Pause: at this point, ask yourself the following questions:

- Why did you seek the feedback before submitting?

- How did you choose the readers?

- What is your reaction to the three different responses?

Imposter syndrome induces a state of self-questioning and hesitation in the face of risk. Here the initial risk is rejection by a (potentially prestigious) journal. Seeking input during the development stage of a project can be helpful; but when we look for feedback on something we think is ready to submit we may in fact we looking for reassurance to help minimise our sense of anxiety. Having sought feedback, another risk emerges, of rejection by peers who you know and connect with on a regular basis. This risk is usually more acute as it carries a potential to feel a renewal of shame whenever interacting with these colleagues in future. The more intense emotions we feel at their responses generate further personalisation. If we were seeking reassurance from the feedback, we are more likely to agree with the critical reviewers as they seem to confirm that there is a risk to submission that we can mitigate with more work. So, we go back to the article and redraft, probably revising the framework and also tackling the extensive reading list. More months go past and the article remains unfinished on our desk, no closer to submission.

Pause: and ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the article still resemble the project you originally set out to write?

- Why was the feedback different from each reader?

- Have the changes you made helped you to feel more confident?

- And… what about the positive feedback, why did you automatically discount it?

Recovering from imposter syndrome requires that we take note of external circumstances, AND re-evaluate our own internalised beliefs. This can be done with the help of tools like CBT, and I offer input and support through my coaching programmes and workshops. But here is a simple place to start – when your notice that your body is reacting and become agitated or heavy, that your emotions are feeling frantic or low, and that your thoughts have shifted to self-doubt and worry…STOP. S: stop reacting; T: take a breath, notice your body, and move in a way that is calming; O: observe your thoughts, perhaps write them down, challenge any that are not evidence based or are highly critical; P: proceed mindfully, having come back into full integration choose how to respond in your best interest.

If you struggle with imposter syndrome and find it debilitating, I have spaces open now for coaching in the autumn. Just get in touch using the form below. Or come along to one of my monthly workshops to learn tools and find community with other academics looking to change the ways we relate to the sector.

If you have appreciated this blog, please consider supporting me through Buy Me a Coffee, a simple way to support freelancers to produce open access content.

Leave a reply to Workplace trauma and the ‘second violence’ – Beatha Coaching Cancel reply